| 일 | 월 | 화 | 수 | 목 | 금 | 토 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

- 뇌과학

- 머신러닝

- steve jobs

- 정책

- McKinsey

- Machine Learning

- 스티브 잡스

- 경제학

- 맥킨지

- 컨설팅펌

- 산후조리원 2주 요금

- 산후조리원 요금

- 조리원 2주 가격

- 박근혜

- 박근혜 대통령

- 산후조리원 2주 가격

- 창조 경제

- 창조경제

- 조리원 2주 요금

- 미래창조과학부

- 정책 자료집

- 전속계약효력정지가처분

- 카카오

- 정책 모음집

- 2009카합2869

- 박근혜 정부

- 문화체육관광부

- 기계

- McKinsey Quarterly

- M&A

- Today

- Total

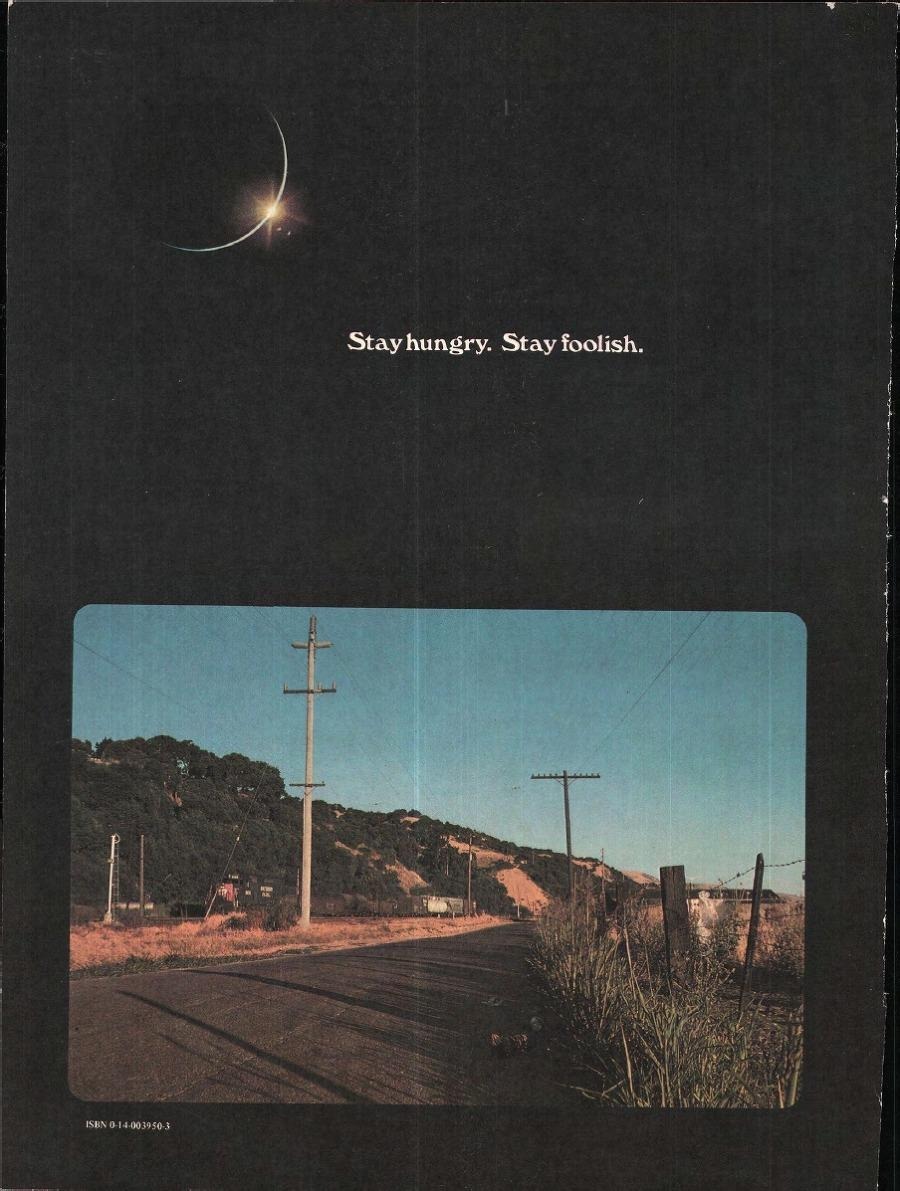

Whole Earth Catalog

Is Culture Destiny? 본문

Is Culture Destiny?

The Myth of Asia's Anti-Democratic Values

In his interview with Foreign Affairs (March/April 1994), Singapore's former prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, presents interesting ideas about cultural differences between Western and East Asian societies and the political implications of those differences. Although he does not explicitly say so, his statements throughout the interview and his track record make it obvious that his admonition to Americans "not to foist their system indiscriminately on societies in which it will not work" implies that Western-style democracy is not applicable to East Asia. Considering the esteem in which he is held among world leaders and the prestige of this journal, this kind of argument is likely to have considerable impact and therefore deserves a careful reply.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, socialism has been in retreat. Some people conclude that the Soviet demise was the result of the victory of capitalism over socialism. But I believe it represented the triumph of democracy over dictatorship. Without democracy, capitalism in Prussian Germany and Meiji Japan eventually met its tragic end. The many Latin American states that in recent decades embraced capitalism while rejecting democracy failed miserably. On the other hand, countries practicing democratic capitalism or democratic socialism, despite temporary setbacks, have prospered.

In spite of these trends, lingering doubts remain about the applicability of and prospects for democracy in Asia. Such doubts have been raised mainly by Asia's authoritarian leaders, Lee being the most articulate among them. They have long maintained that cultural differences make the "Western concept" of democracy and human rights inapplicable to East Asia. Does Asia have the philosophical and historical underpinnings suitable for democracy? Is democracy achievable there?

SELF-SERVING SELF-RELIANCE

Lee stresses cultural factors throughout his interview. I too believe in the importance of culture, but I do not think it alone determines a society's fate, nor is it immutable. Moreover, Lee's view of Asian cultures is not only unsupportable but self-serving. He argues that Eastern societies, unlike Western ones, "believe that the individual exists in the context of his family" and that the family is "the building brick of society." However, as an inevitable consequence of industrialization, the family-centered East Asian societies are also rapidly moving toward self-centered individualism. Nothing in human history is permanent.

Lee asserts that, in the East, "the ruler or the government does not try to provide for a person what the family best provides." He cites this ostensibly self-reliant, family-oriented culture as the main cause of East Asia's economic successes and ridicules Western governments for allegedly trying to solve all of society's problems, even as he worries about the moral breakdown of Western societies due to too much democracy and too many individual rights. Consequently, according to Lee, the Western political system, with its intrusive government, is not suited to family-oriented East Asia. He rejects Westernization while embracing modernization and its attendant changes in lifestyle - again strongly implying that democracy will not work in Asia.

FAMILY VALUES (REQUIRED HERE)

But the facts demonstrate just the opposite. It is not true, as Lee alleges, that Asian governments shy away from intervening in private matters and taking on all of society's problems. Asian governments intrude much more than Western governments into the daily affairs of individuals and families. In Korea, for example, each household is required to attend monthly neighborhood meetings to receive government directives and discuss local affairs. Japan's powerful government constantly intrudes into the business world to protect perceived national interests, to the point of causing disputes with the United States and other trading partners. In Lee's Singapore, the government stringently regulates individuals' actions - such as chewing bubble-gum, spitting, smoking, littering, and so on - to an Orwellian extreme of social engineering. Such facts fly in the face of his assertion that East Asia's governments are minimalist. Lee makes these false claims to justify his rejection of Western-style democracy. He even dislikes the one man, one vote principle, so fundamental to modern democracy, saying that he is not "intellectually convinced" it is best.

Opinions like Lee's hold considerable sway not only in Asia but among some Westerners because of the moral breakdown of many advanced democratic societies. Many Americans thought, for example, that the U.S. citizen Michael Fay deserved the caning he received from Singaporean authorities for his act of vandalism. However, moral breakdown is attributable not to inherent shortcomings of Western cultures but to those of industrial societies; a similar phenomenon is now spreading through Asia's newly industrializing societies. The fact that Lee's Singapore, a small city-state, needs a near-totalitarian police state to assert control over its citizens contradicts his assertion that everything would be all right if governments would refrain from interfering in the private affairs of the family. The proper way to cure the ills of industrial societies is not to impose the terror of a police state but to emphasize ethical education, give high regard to spiritual values, and promote high standards in culture and the arts.

LONG BEFORE LOCKE

No one can argue with Lee's objection to "foisting" an alien system "indiscriminately on societies in which it will not work." The question is whether democracy is a system so alien to Asian cultures that it will not work. Moreover, considering Lee's record of absolute intolerance of dissent and the continued crackdown on dissidents in many other Asian countries, one is also compelled to ask whether democracy has been given a chance in places like Singapore.

A thorough analysis makes it clear that Asia has a rich heritage of democracy-oriented philosophies and traditions. Asia has already made great strides toward democratization and possesses the necessary conditions to develop democracy even beyond the level of the West.

Democratic Ideals. It is widely accepted that English political philosopher John Locke laid the foundation for modern democracy. According to Locke, sovereign rights reside with the people and, based on a contract with the people, leaders are given a mandate to govern, which the people can withdraw. But almost two millennia before Locke, Chinese philosopher Meng-tzu preached similar ideas. According to his "Politics of Royal Ways," the king is the "Son of Heaven," and heaven bestowed on its son a mandate to provide good government, that is, to provide good for the people. If he did not govern righteously, the people had the right to rise up and overthrow his government in the name of heaven. Meng-tzu even justified regicide, saying that once a king loses the mandate of heaven he is no longer worthy of his subjects' loyalty. The people came first, Meng-tzu said, the country second, and the king third. The ancient Chinese philosophy of Minben Zhengchi, or "people-based politics," teaches that "the will of the people is the will of heaven" and that one should "respect the people as heaven" itself.

A native religion of Korea, Tonghak, went even further, advocating that "man is heaven" and that one must serve man as one does heaven. These ideas inspired and motivated nearly half a million peasants in 1894 to revolt against exploitation by feudalistic government internally and imperialistic forces externally. There are no ideas more fundamental to democracy than the teachings of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Tonghak. Clearly, Asia has democratic philosophies as profound as those of the West.

Democratic Institutions. Asia also has many democratic traditions. When Western societies were still being ruled by a succession of feudal lords, China and Korea had already sustained county prefecture systems for about 2,000 years. The government of the Chin Dynasty, founded by Chin-shih huang-ti (literally, the founder of Chin), practiced the rule of law and saw to it that everyone, regardless of class, was treated fairly. For nearly 1,000 years in China and Korea, even the sons of high-ranking officials were not appointed to important official positions unless they passed civil service examinations. These stringent tests were administered to members of the aristocratic class, who constituted over ten percent of the population, thus guaranteeing equal opportunity and social mobility, which are so central to popular democracy. This practice sharply contrasted with that of European fiefdoms of that time, where pedigree more or less determined one's official position. In China and Korea powerful boards of censors acted as a check against imperial misrule and abuses by government officials. Freedom of speech was highly valued, based on the understanding that the nation's fate depended on it. Confucian scholars were taught that remonstration against an erring monarch was a paramount duty. Many civil servants and promising political elites gave their lives to protect the right to free speech.

The fundamental ideas and traditions necessary for democracy existed in both Europe and Asia. Although Asians developed these ideas long before the Europeans did, Europeans formalized comprehensive and effective electoral democracy first. The invention of the electoral system is Europe's greatest accomplishment. The fact that this system was developed elsewhere does not mean that "it will not work" in Asia. Many Asian countries, including Singapore, have become prosperous after adopting a "Western" free-market economy, which is such an integral part of a democracy. Incidentally, in countries where economic development preceded political advancement - Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain - it was only a matter of time before democracy followed.

The State of Democracy in Asia. The best proof that democracy can work in Asia is the fact that, despite the stubborn resistance of authoritarian rulers like Lee, Asia has made great strides toward democracy. In fact, Asia has achieved the most remarkable record of democratization of any region since 1974. By 1990 a majority of Asian countries were democracies, compared to a 45 percent democratization rate worldwide.[1] This achievement has been overshadowed by Asia's tremendous economic success. I believe democracy will take root throughout Asia around the start of the next century. By the end of its first quarter, Asia will witness an era not only of economic prosperity, but also of flourishing democracy.

I am optimistic for several reasons. The Asian economies are moving from a capital- and labor-intensive industrial phase into an information- and technology-intensive one. Many experts have acknowledged that this new economic world order requires guaranteed freedom of information and creativity. These things are possible only in a democratic society. Thus Asia has no practical alternative to democracy; it is a matter of survival in an age of intensifying global economic competition. The world economy's changes have already meant a greater and easier flow of information, which has helped Asia's democratization process.

Democracy has been consistently practiced in Japan and India since the end of World War II. In Korea, Burma, Taiwan, Thailand, Pakistan, the Philippines, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and other countries, democracy has been frustrated at times, even suspended. Nevertheless, most of these countries have democratized, and in all of them, a resilient "people power" has been demonstrated through elections and popular movements. Even in Thailand, after ten military governments, a civilian government has finally emerged. The Mongolian government, after a long period of one-party dictatorship, has also voluntarily accepted democracy. The fundamental reason for my optimism is this increasing awareness of the importance of democracy and human rights among Asians themselves and their willingness to make the necessary efforts to realize these goals. Despite many tribulations, the torch of democracy continues to burn in Asia because of the aspirations of its people.

WE ARE THE WORLD

As Asians increasingly embrace democratic values, they have the opportunity and obligation to learn from older democracies. The West has experienced many problems in realizing its democratic systems. It is instructive, for example, to remember that Europeans practiced democracy within the boundaries of their nation-states but not outside. Until recently, the Western democracies coddled the interests of a small propertied class. The democracies that benefited much broader majorities through socioeconomic investments were mostly established after World War II. Today, we must start with a rebirth of democracy that promotes freedom, prosperity, and justice both within each country and among nations, including the less-developed countries: a global democracy.

Instead of making Western culture the scapegoat for the disruptions of rapid economic change, it is more appropriate to look at how the traditional strengths of Asian society can provide for a better democracy. In Asia, democracy can encourage greater self-reliance while respecting cultural values. Such a democracy is the only true expression of a people, but it requires the full participation of all elements of society. Only then will it have legitimacy and reflect a country's vision.

Asian authoritarians misunderstand the relationship between the rules of effective governance and the concept of legitimacy. Policies that try to protect people from the bad elements of economic and social change will never be effective if imposed without consent; the same policies, arrived at through public debate, will have the strength of Asia's proud and self-reliant people.

A global democracy will recognize the connection between how we treat each other and how we treat nature, and it will pursue policies that benefit future generations. Today we are threatening the survival of our environment through wholesale destruction and endangerment of all species. Our democracy must become global in the sense that it extends to the skies, the earth, and all things with brotherly affection.

The Confucian maxim Xiushen qijia zhiguo pingtianxia, which offers counsel toward the ideal of "great peace under heaven," shows an appreciation for judicious government. The ultimate goal in Confucian political philosophy, as stated in this aphorism, is to bring peace under heaven (pingtianxia). To do so, one must first be able to keep one's own household in order (qijia), which in turn requires that one cultivate "self" (xiushen). This teaching is a political philosophy that emphasizes the role of government and stresses the ruling elite's moral obligation to strive to bring about peace under heaven. Public safety, national security, and water and forest management are deemed critical. This concept of peace under heaven should be interpreted to include peaceful living and existence for all things under heaven. Such an understanding can also be derived from Gautama Buddha's teaching that all creatures and things possess a Buddha-like quality.

Since the fifth century B.C., the world has witnessed a series of revolutions in thought. Chinese, Indian, Greek, and Jewish thinkers have led great revolutions in ideas, and we are still living under the influence of their insights. However, for the past several hundred years, the world has been dominated by Greek and Judeo-Christian ideas and traditions. Now it is time for the world to turn to China, India, and the rest of Asia for another revolution in ideas. We need to strive for a new democracy that guarantees the right of personal development for all human beings and the wholesome existence of all living things.

A natural first step toward realizing such a new democracy would be full adherence to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations in 1948. This international document reflects basic respect for the dignity of people, and Asian nations should take the lead in implementing it.

The movement for democracy in Asia has been carried forward mainly by Asia's small but effective army of dedicated people in and out of political parties, encouraged by nongovernmental and quasi-governmental organizations for democratic development from around the world. These are hopeful signs for Asia's democratic future. Such groups are gaining in their ability to force governments to listen to the concerns of their people, and they should be supported.

Asia should lose no time in firmly establishing democracy and strengthening human rights. The biggest obstacle is not its cultural heritage but the resistance of authoritarian rulers and their apologists. Asia has much to offer the rest of the world; its rich heritage of democracy-oriented philosophies and traditions can make a significant contribution to the evolution of global democracy. Culture is not necessarily our destiny. Democracy is.

FOOTNOTE

[1] Samuel Huntington, The Third Wave, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.

'[2] scrap' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Steve Jobs, Apple 사임서 (1) | 2016.02.22 |

|---|---|

| 법정스님, 아름다운 마무리 中 (0) | 2016.02.22 |

| 백석과 자야, 사랑과 이별의 긴 숨바꼭질 (2010) (0) | 2016.02.22 |

| A Conversation with Lee Kuan Yew (0) | 2016.02.22 |

| 문정희, “나는 천재의 것이 좋다” (0) | 2016.02.22 |

Is Culture Destiny.pdf

Is Culture Destiny.pdf